Case study of Urban Slum Dwellers of Kalyani, West Bengal:

A popular conception in spatial and socio-economical studies across the world exists that a person is vulnerable if he/she has no money and hence cannot access resources, thereby slipping into poverty. However, in his seminal work, “The Idea of Justice”, Dr. Amartya Sen breaks this misconception by suggesting that poverty is a composite function of resources (natural, political, economic etc.) available in the surrounding of the person, linkages (political, social, economic etc.) and the ease of access to such linkages. This would mean that even if a person/family has lower income, its superior access to key people and resources has the capacity to pull it out of vulnerability.

Land is the biggest resource

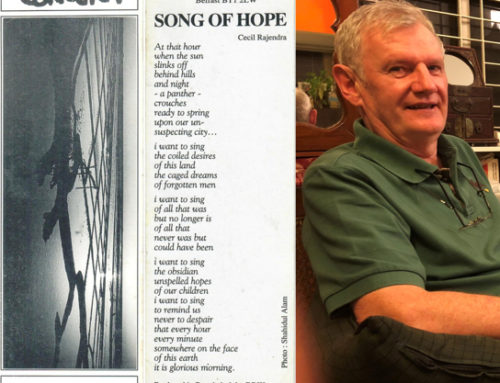

Geeta Biswas pointing out to an open defecation map in a triggering exercise in Vidyasagar Colony. Photo: Amit Sengupta/CLTS Foundation

The biggest resource is land and is the core issue of all urban planning genres. Its possession and utilization has become immensely contentious and heavily politicized. Such problems achieve superlative proportion in urban context.

Slums have been a common phenomena in all cities and is being increasingly considered a failure of urban planning policies of states. Their unauthorised and illegal existence is enough to exclude them from sanitation and other basic services that the Human Rights Commission proclaims non-negotiable. Since time immemorial, slum evictions have taken place in all major cities on grounds of unhygienic conditions. A mid-way of non-eviction of slums and maintenance of healthy environs meant granting legal tenure to slum dwellers. However, it has been seen in certain cases, that slum-dwellers act strategically to access security of land tenure (either de-facto or de-jure). These actions could range from mutual understanding among slum residents to political patronage or subscribing to government projects.

Objective of the Research Paper

The core objective of the paper is:

- To understand land tenure system in slums of a town/city

- How they perceive their right to land

- To unearth strategies slum dwellers employ to claim de-facto land tenure

- To understand the role of documents in claiming land rights

- To ascertain the role of sanitation in their strategy to claim land rights

- To establish the role of Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) in solidifying their claim to land rights

Kalyani Municipality in West Bengal is the first open defecation free township in India. Photo by CLTS Foundation

With such concepts and objectives in mind, two slums in Kalyani (Nadia District), West Bengal, India were chosen as a case study. This is because, firstly, Kalyani had been awarded for being the first open defecation free (ODF) city in the country. Subsequently, under Mission Nirmal Bangla (Govt. of West Bengal’s version of Swachh Bharat Mission), Nadia district was awarded the first ODF District in the state of West Bengal. Considering that the Kalyani Municipality does not own land but has the burden of providing basic services of water, sanitation and electricity to all its citizens, more than 50% of the urban population lives in slums and many refugees from erstwhile East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) have settled in its various wards makes it an interesting case study.

Case Study of urban slums of Kalyani in West Bengal, India

In Kalyani, Harijan Pally (Ward-4) and Vidyasagar Para (Ward-1) were chosen as case studies. While Harijan Pally is located in the core of the city, Vidyasagar is in the periphery of this urban township. Harijan Pally has 83 households (359 people), while Vidyasagar has 295 households (1218 people). Although both the slums are notified (though no notification system exists with the municipality presently), Harijan Pally is located on Kalyani University land while Vidyasagar Para is located on Industrial Land. Interestingly, land is owned by the Estate Manager here and the Municipality has no control over it. Hence, the municipality (being a constitutional body with a mandate of providing basic services and liveable environment to all its residents according to 74th Constitutional Amendment Act, 1992) has limited power when it comes to legalising slums.

Although the settlements lack legal land tenure, they have a detailed system of informal land ownership primarily by Abaasi Patra issued by Municipal Councillor (having no legal value). Other documents include ration card, driving license, electricity bills, voter IDs, Aadhar Cards. These documents together provide a sense of legitimacy to any external observer and hence, helps consolidate security of tenure.

Use of Community-Led Total Sanitation to claim land rights

In Harijan Pally, the ownership of land is with the Kalyani University (KU). However, in 2009, the Vice Chancellor of KU gave a No Objection Certificate (NOC) to the Kalyani Municipality to use the parcel of land for developmental purposes. However, since all state university lands are owned by the Ministry of Higher Education (GoWB), the land ownership is still in doldrums. Conversely, in Vidyasagar Para, land is owned by industries and the government has shown no intention of giving away the property rights. However, residents claim that Pattas (deeds) have been distributed in neighbouring slums. Although, the situation is uncertain, this hasn’t stopped the residents of either slums to not develop their settlement. While in Harijan Pally, layout re-organisation has occurred after the implementation of Community –Led Total Sanitation in 2005 showed them that anything can be achieved through collective action. Not only have they measured and redistributed land among themselves in their settlement, they have also chalked out future plans (albeit informal) of amenities they intend to construct in their settlement and overall development of their neighbourhood. In Vidyasagar Para, women’s groups have again been formed to start savings group after the success of CLTS. A Shishu Shiksha Kendra (Child Learning Centre) has been built in the settlement through government funds to educate local children in Harijan Pally. In Vidyasagar Para, roads and drains have been built by womens’ savings groups’ investments.

The indicators that signify the change in perception of security of land tenure are clear in either of these two slums. While in Harijan Pally, land has been set aside for development of various amenities like community hall and football field, women in Vidyasagar Para have come together to create savings group to refurbish their houses and toilets once they are legalised. In Harijan Pally, sanitary facilities are kept clean and maintained regularly and a general optimism can be sensed regarding Swachh Bharat Mission. Also, slum dwellers have come together to undertake various repair-works in the settlements to avoid creation of slum-like situations that further prove disadvantageous to their legalisation of land-occupation. Children in either settlements are being increasingly sent to school, now that they have papers that can prove their residency.

In a curious case and showcasing a way when formal state-sponsored actions can create positive sense of security of tenure, the government, under Sobar Shauchagar (Toilets for All), has provided permanent toilets with concrete roofs to households in Harijan Pally when according to the same government’s mandate, one is not supposed to make their roofs permanent if they reside on land illegally. This dichotomy of state further create impressions of security of land tenure among its residents. Interestingly, the Sobar Souchagar is a programme specifically for rural areas that are characterised by legal land tenure of beneficiary. Since the toilets provided are in the slums that are ‘notified’ by the municipality (hence, in urban location), would mean that the owner of the toilets have legal land tenure (albeit in rural area adjoining Kalyani).

Tathabrata Bhattacharya is a student of M.Sc. UEP/UDR, 2015-17, NTNU, Trondheim, Norway. He was on a 2 months internship with Community Led Total Sanitation Foundation, Kolkata, India. This blog is based on his research paper as part of his studies. The views expressed by the author are his own. It doesn’t necessarily reflect the views of CLTS Foundation.

Also Read – Related Research Paper:

Impact of CLTS on Women’s Health in Urban Slums: A Case Study from Kalyani Municipality

Must Read related blogs:

Leave A Comment